The Ever-Loving Question: Why Steel?

Joy in Steel

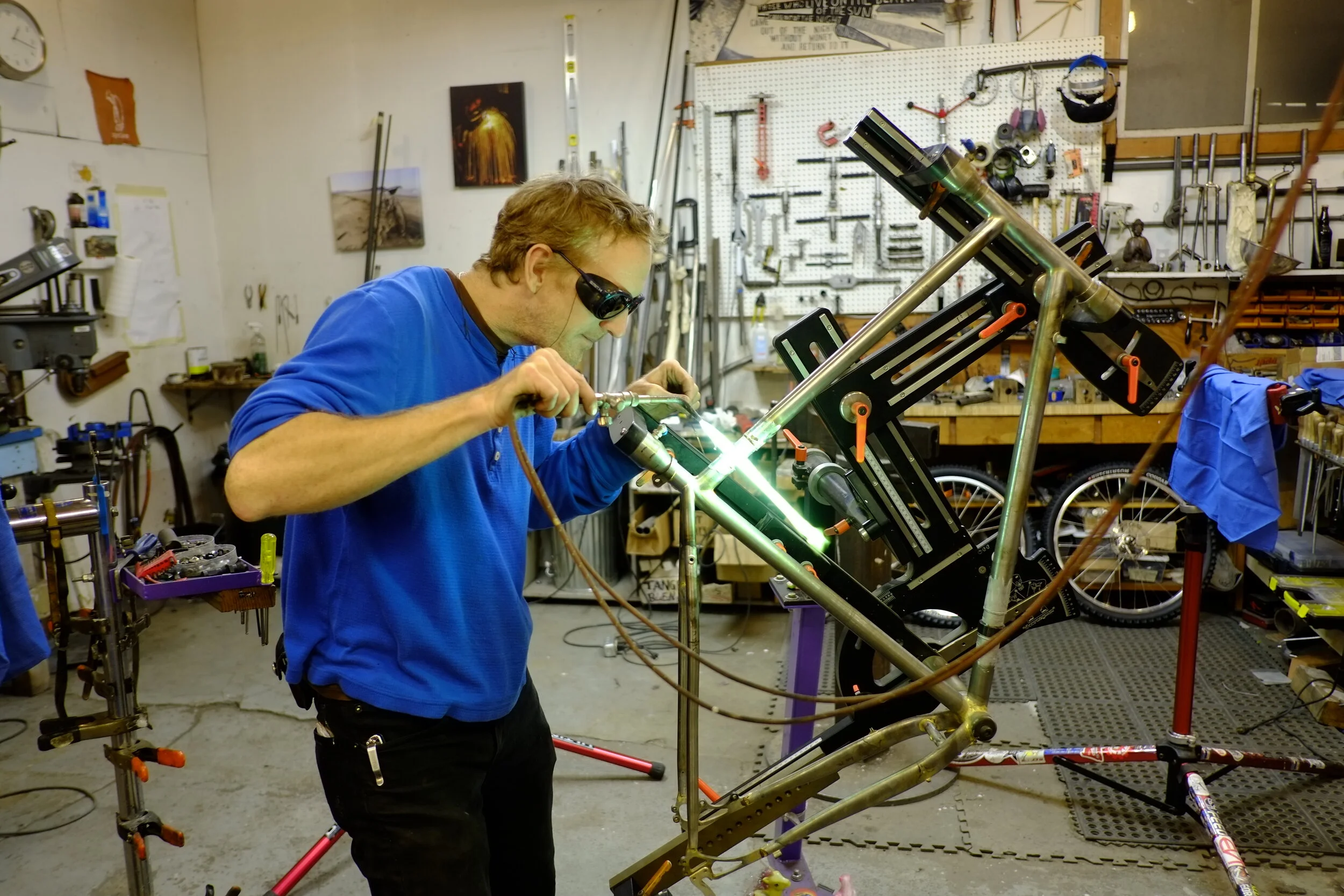

Recently, I’ve been asked why I use steel for building bicycle frames. I’ve been building steel bikes for so long, and I’m so immersed in it as my material of choice that I forget that this conversation sometimes needs to happen.

The short answer is: I use steel is because I believe it’s the material best suited to the kinds of bikes I build. There are a lot of different types of bikes and styles of riding, and I won’t claim to know what’s best for everything, and everyone. I only know my own experience, and my methods of bike construction, and the time I’ve spent in the saddle, riding bikes in various situations — touring, commuting, road rides, off-road, city meandering and neighborhood exploration.

What’s It Made Of?

The four main materials used for bike frames are steel, titanium, carbon fiber, and aluminum, and I believe each has their place, their “genre” of bike, exploiting each material’s best attributes. Steel and aluminum are the most commonly used for bicycle frames, and they’re the most versatile. But steel has, in my opinion, the widest range of desirable attributes. If you want to read more, here’s an interesting blog post that compares steel and aluminum.

As a custom bicycle maker, I like options. When I’m designing a frame for a person, I take into account a lot of variables, including the rider’s size and strength, their flexibility, as well as what they tell me they’re going to do with the bike, what they’ll expect from it, where they think they’ll go, what they’ll carry, and so on. Based on this overall picture, I design the bike and choose each individual tube to try and balance all the demands, and bring out the best qualities.

Each manufacturer of steel tubing offers their own versions of heavier, stronger, and lighter tubes, harder and “softer” materials, varied butt lengths, cold-rolled, heat-treated, welded seams or drawn tubes, etcetera, each of which has different properties for construction, for ride quality, weight, and cost.

What’s Weight Got to Do With It?

What’s Under the Paint

In regards to weight, I forget that some people still have the perception that if a bike is made from steel, it must be heavy. There is some amazing steel tubing available, extremely thin-walled, hard, and incredibly strong. It’s not too difficult to build a steel bike at or below eighteen pounds. Depending on the size and strength of the rider, and how much money they want to spend, it could go lighter. Eighteen pounds may sound heavy these days when compared with carbon fiber bikes that push toward ten or twelve pounds, but a twelve-pound carbon bike tends to have a fairly specific purpose, and is not, in my opinion, a bike most people really need.

In the Real World

Carbon fiber and aluminum bicycles have finite lives. If properly cared for, a steel frame will last much longer, potentially a lifetime. This has to do with the inherent flexibility of steel, which is one of its greatest attributes, and one of the main reasons why it is considered such a desirable material for bikes. Steel accepts rider inputs and road vibration, dispersing these over the span of the frame, and doesn’t so readily translate into rider fatigue, and, over time, frame fatigue. It creates a relationship between the rider and the ride, giving a bit of snap to the acceleration and carve to the turns. It’s this same flexibility that prevents a steel frame from wearing out.

Without going too deeply into physics or metallurgy — subjects I’m not qualified to discuss for more than about 30 seconds — what we’re talking about when we talk about frame flex is the material’s elasticity. What makes steel so interesting is that there’s a balance, a “sweet spot,” between its weight and flexibility.

Building bikes out of steel

Bent Tubes

When we reach the end of a material’s ability to flex, we’ve arrived at its “yield point,” which is its point of no return. This is when you’ve bent the material so far that it won’t ever bend back to exactly where it was, to “straight.” What happens is that the molecules have stretched beyond their ability to return to where they started.

Let’s translate this to everyday riding: Every time you push on the pedals, hit a bump, load your bike with gear and take a hard corner, stand up out of the saddle to crush it up a hill, and so on, you are stressing your bike frame.

Whereas steel will flex and absorb these stresses, carbon and aluminum frames gradually, incrementally, microscopically, become weaker and weaker. Over time, these inputs will cause aluminum and carbon frames to lose their rigidity, and eventually, they will become soft, noodly, and inefficient. And, especially with aluminum, it will finally crack. This may take years. But if the bike is being ridden, it will happen.

Titanium Hardtail MTB

I don’t talk too much about titanium here because I consider it to be in a class by itself. It’s an amazing material, but it presents several barriers to use for general purpose bikes. It has the most elasticity, meaning it’s incredibly flexible, which can be beneficial, or detrimental, depending on what you want the bike to do. It doesn’t corrode, and it’s very light, but it is much more expensive to manufacture than the other materials, and the way it flexes limits its versatility. But, for the bikes it works for, it works extremely well. The ti bike I most want is a hardtail mountain bike.

Gravity’s Rainbow

Lay It Out

Getting back to the discussion of weight: If you compare frames of the same size made from carbon, aluminum, steel, and titanium — frames that were built to do the same job — you will discover that the actual weight range between them is relatively small. Probably within a couple of pounds. If you’re talking about a road racing bike, this may make a difference, but if you’re talking about touring or commuting bikes, this additional weight matters much less.

One major problem with comparing frame weight is that each material lends itself to certain kinds of bikes, so there aren’t all that many ways we can draw meaningful comparisons. Carbon fiber touring bike? This doesn’t sound like a good idea. Steel competition road bike? In the not-too-distant past, yes, but those days are likely over. Titanium full-suspension downhill bike? Possibly, but I can’t imagine the cost of machining all the hardware for the suspension mounts and pivots, and, in the end, so what? — aluminum is probably as good for this application, and it’s way cheaper.

Also important to think about — for a relatively traditional bike, the frame only makes up about a quarter or less of the overall weight. So if you’re going to talk about weight, you’ve got to talk about the components. The single greatest upgrade that I’ve made to my bike over the past few years was to switch to carbon wheels. I was a purist for a long time, a nay-sayer to anything carbon. But then I bought some Rolf Prima wheels for a show bike and afterward when I rode them, it was like, Oh my. This transformed my mid-weight gravel bike into something so light and fast that when I first rode it I felt like a superhero. It was amazing.

Design & Components Matter Most

For me, I think the main issue with talking about bike weight is, there is almost no correlation between weight and ride quality. A bike rides well because of choices made in its construction, including the material used, the geometry of the bike, front end design, chainstay length, and bottom bracket drop, etcetera. Ride quality, in my opinion, is so much more important than weight. And steel bikes — especially the ones made custom — bring these positive qualities forward like no other material.

As with everything, there’s a balance to be stricken, and if you don’t know for sure, you could go discuss frame materials and components with someone at your local bike shop. Ask questions. And whatever you hear, take it with a grain of salt — everyone has their experience and their knowledge base and their own special bias. The only subject I can think of that’s lousier with bias might be politics.

Clearly No Bias

Speaking of which, are you registered to vote? If not, please do so. And vote. Then make sure everyone you know has voted, too. If you’re not sure how or where to register, here’s a link.

Get out and Ride

The Most Important Thing

Of course, and lastly, the most important way to learn about bike materials is to ride your bike. If you’re paying attention, the bike you are riding is going to give you so much information. Do you like it? Could you like it more? How so?

If you would like to discuss options for a ride that might suit you, feel free to send me a message. But be forewarned — we can talk about all sorts of things related to bikes and life and whatever, but I may not want to talk much about frame weight. Or, for that matter, politics.

Thank you for reading!