Christopher Igleheart is retiring!

Christopher Igleheart, photo credit: Dylan VanWeelden

The master welder behind Igleheart Custom Frames & Forks is hanging up his TIG torch and moving on into his next phase of life. And, no less, he and his wife are moving to France!

Please mark your calendar and come to his send-off gathering:

Friday, August 5, 2022, from 4 - 7 pm in the Breadwinner Cycles parking lot, on Page St. in North Portland. There’ll be some beer, possibly some snacks. Bring a bike, bring friends, bring good cheer and let’s send off this legend of US bike building in style!

Some Bicycle History & Other Stuff

The history of bespoke bicycle making in the USA is mostly negligible until the “invention” of mountain bikes. Similar to almost any other invention, nothing about mountain bikes was completely new. It was more of a rearrangement and adaptation of already existing technologies — of fat tires and old bike frames, flat bars, dirt & gravity.

In this case, in the 1970s, some adrenaline fueled kids in Marin County, California, put together these various components and bombed down Mt. Tamalpais. From the bottom, shaking with joy, they rode back to the top and did it again. And again. They found this to be so exceedingly fun that they immediately began modifying & improving all aspects of these improvised bikes — frames, brakes, gearing — and in the process birthed an industry that would in a few years be worth billions.

By all accounts, this new sport of mountain biking started at Mt. Tam in the west. Someone had to bring it across to the East Coast, and one of the main players in doing so was a guy named Chris Chance. In 1982 Chance started a bicycle frame manufacturing company called Fat City Cycles in Somerville, Massachusetts. At the beginning, in 1981-82, Fat City wasn’t officially in business. It was, according to Christopher Igleheart, just few friends of Chris Chance. They built a dozen or so bikes and took them to a trade show in New York that spring to see if they’d sell. They did, and they took a few orders besides, and with that the business began. Its first bike, dubbed the Fat Chance, was designed for riding the tight switchback trails with roots, rocks and sharp climbs that were common throughout New England.

In the early 1970s, Chris Chance had been a part of Whitcomb USA, a satellite of Whitcomb UK, a bespoke steel bicycle maker. This was a short lived venture with two of the grand masters of US bike building — Peter Weigle & Richard Sachs — both of whom had traveled to the UK to learn the craft of hand making bicycle frames.

At that time all bicycles were built from steel and there were, in a sense, two trajectories that one could take to construct a bicycle frame — brazing, or TIG welding. Brazing is a way of adding a filler material, usually brass or silver, essentially “gluing” tubes together with molten metal. TIG welding involves melting the actual steel to fuse one tube to another. Traditionally, and to this day, brazing is considered a slower process, craftier, more artisanal, whereas TIG welding gets the job done more efficiently and better lends itself to production. Neither process is superior to the other — a properly built bicycle will be strong, will ride well (if designed well), and last a long time, no matter how the tubes are stuck together. The only significant difference is the aesthetic, and the time it takes to do the job.

Both Peter Weigle and Richard Sachs learned the traditional craft of brazing frames and have stayed with this process throughout their careers. Chris Chance saw opportunity in volume rather than in individual details, and with the help of welder, fabricator, and wild genius (and former roadie for Aerosmith), Gary Helfrich, Chance moved toward TIG welding & volume manufacturing rather than one-off designs. As a teacher of the craft of frame building, Chance had exactly one official student, our man, Christopher Igleheart.

Historical artifact #23

At the time, Christopher was the owner of a small bike shop in Portland, Maine, called the Portland Bicycle Exchange. It was a neighborhood repair shop that he’d opened in 1975. Anyone tapped into the world of cycling had heard of this new craze of bikes with big tires that you could ride off road. But the problem, before Fat City Cycles, was getting ahold of one. East Coasters had to patch them together out of whatever they could find just like the Mt. Tam crowd had done.

In 1982, Igleheart started working part time at Fat City Cycles as a novice welder. As any welder will tell you, the only way to learn it is to put in hours with the torch, and Igleheart got his chops making hundreds of box crown forks. For the next 4 years he split his time between his bike shop, where he built wheels for these new mountain bikes, and welding for Fat City. Finally, in 1986 he sold his bike shop and started working at Fat City full time, further honing his welding skills and engaging in the whole process of bike making. In 1986 he was one of about 10 employees, and by the early 90s, at their peak, Fat City had around 30 workers, mostly young people.

These kids at Fat City Cycles found themselves at the forefront of a booming industry. Schwinn had been the reigning king of US bike manufacturing for so long and they totally missed the boat with mountain bikes, thinking it was a passing fad. By the time Schwinn figured it out it was too late to retool their massive factory, and companies like Fisher and Specialized and the more off-beat Fat City Cycles took over the market. Schwinn lost brand credibility, had internal problems, didn’t invest in modernizing production, all of which contributed to their fall. In 1992 they declared bankruptcy.

Another interesting piece of this story is, mountain bikes became popular during the same period when so much of American manufacturing was being exported overseas. This included much, but not all, of bicycle production as well. I imagine there’s an argument to be made that the hands-on education that young people received at small and mid-sized facilities like Fat City Cycles is part of the reason why certain kinds of manufacturing still exist as they do on US soil.

So much of manufacturing is hidden away, like under the hood of cars, or mechanical parts encased in appliances, that almost no one sees or thinks about it. With bicycles, though, everything is there in front of you, and it’s all relatively simple, so anyone curious enough can learn what it is, how it works, and with a bit more interest, how it’s made. The accessibility of the bicycle was invitation to many (like me) to become tinkerers and mechanics, sparking enough interest in some of us to take things further.

In a way, bicycles helped give manufacturing a face, and mountain bikes in particular helped make it cool. As Fat City Cycles grew, these young people learned the wider skillset of bicycle making, the “nuts & bolts,” as well as the art, craft, and business of it. Even though exportation of most bike manufacturing set up a competitive imbalance in costs (think unconscionably cheap overseas labor vs. skilled & semi-skilled US labor), it also created a valuable niche market for what was American made, and set the stage for the post-millennium surge of one-off bespoke builders such as myself. But in that time in between, from the early 1980s into the 90s, this one bike brand — Fat City Cycles — introduced dozens of smart, creative young people to the trade, giving them a testing ground to learn all aspects of making things and how to run a business. These were skills that many of them continued to adapt, perfect, and build upon for years to come.

It’s significant to note that several former Fat City employees went on to become influential contributors to the US bicycle industry at large, helping to shape it to this day. Famous people you may never have heard of, like the already-mentioned mad bike-scientist Gary Helfrich, who went on to found Merlin Bikes and who is considered the “grandfather of titanium bicycles;” Rob Vandemark who was a founder of Seven Cycles which continues to be a thriving US bicycle manufacturer; Ron Andrews of King Cage, “Ant Bike” Mike Flanigan; Jeff Buckholtz of Sputnik Tool, and a handful of others. And of course, the bike world also got Christopher Igleheart.

“Forkin’ Off:” Igleheart Fork Building Time-Lapse

Igle

On His Own, and then with Me

Heart

In 1990 Igleheart set out from Fat City and started building bikes under his own name, Igleheart Custom Frames & Forks. He stayed (mostly) on the East Coast for the next twenty-odd years, around the Boston area, and then moved to Portland, Oregon in 2012, which was on the trailing edge of the next wave of popularity of US handmade bicycles. Arriving in Portland, Igleheart worked with Cielo Bikes (of Chris King Precision Components) for a short stint, and then moved his tools onto Page Street, to the workshop where I’d been plying my trade for a few years.

Page Street Cycles

Friends wearing hats: Thank You Smitherman at PDW for the cold-weather swag!

Sharing a workshop over the past decade, Christopher & I periodically teamed up on projects under the name Page Street Cycles, and we both continued building separately under our own names. Our skill sets are different, but complementary — he’s the welder, whereas I braze; he’s got a background in production and I’ve only ever been a one-off bike & rack builder. We’ve both benefitted tremendously from each other’s experience, and are better builders and business people because of our time spent together. Not to mention we became great friends.

Ten years is a long time to get to know someone. He and I would sometimes joke that we ought to be married since we spent way more of our waking hours together at the shop than either of us did with our significant others at home. Sometimes, but not often, we’d bicker like an old couple. Most of the time, though, we got along famously, like Frick & Frack, bantering and laughing at stupid shit that most people would shake their heads at.

Trouble on Page Street - photo credit: Kristina Nash

Christopher & I have a lot of common ground in our unconventional life experiences and we both loved the music that we grew up in. A crucial element in our getting along so well over the past ten years is the crossover we have in our musical tastes. It’s not only that, though. It’s also how we listened that was similar. It wasn’t just the way music set the tone of our workflow, it also holds so many stories, bits of history both cultural and personal, and while listening we compared notes on bands we’d seen or stories from the past or trivia we have about the musicians. It was a central point at the shop, a way of sharing these memories while making new ones.

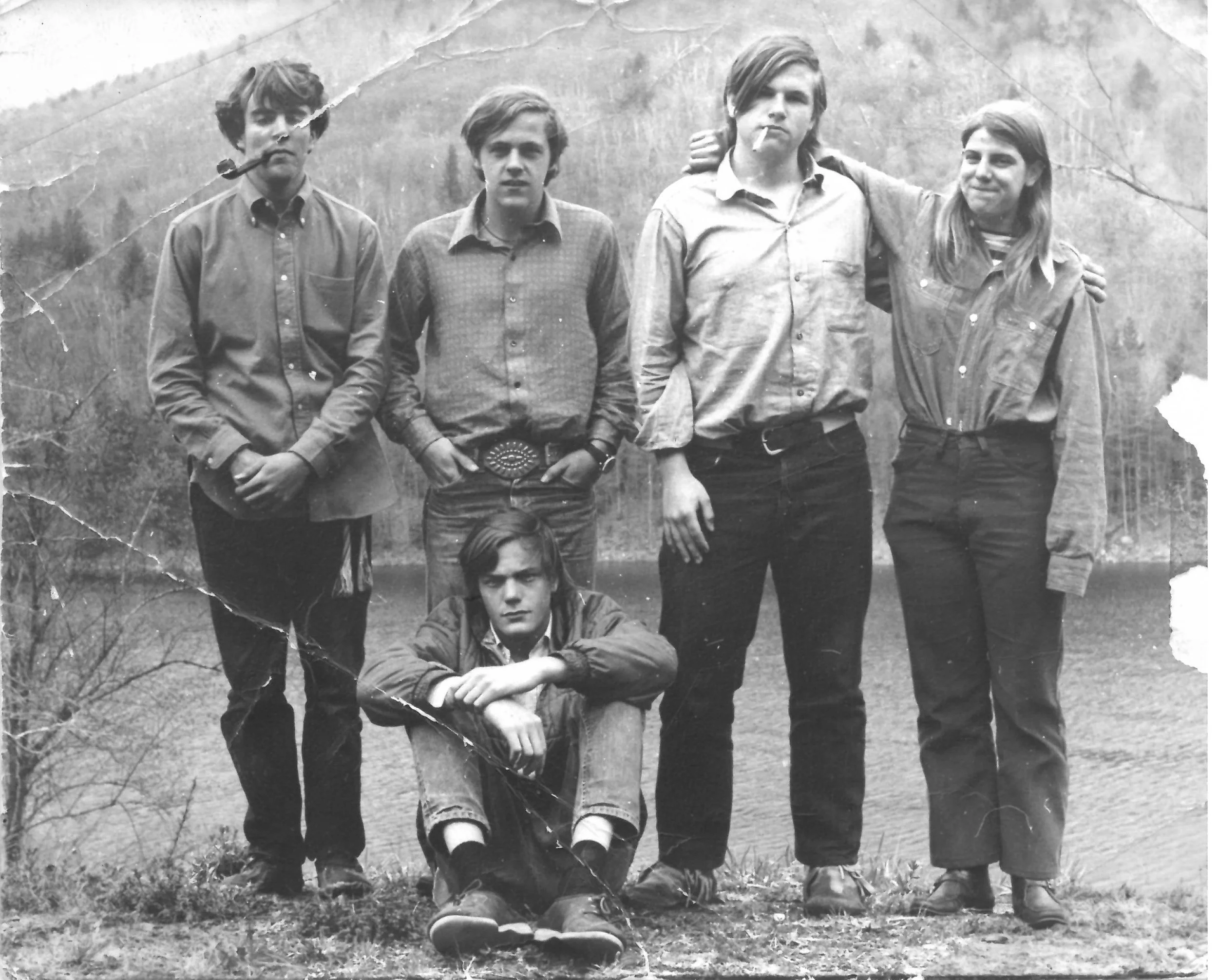

Igleheart & Co., 1969. Can you pick him out? (hint: look at the kid with the pipe…)

As a side note, one of Christopher’s biggest regrets, he tells me, is that he missed seeing Jimi Hendrix play at Woodstock. He saw so many of the greater & lesser bands play there, including Janice Joplin, Santana, Creedence — but he and his friends had been there for three days.

“We were hungry and tired, sick of being in the mud,” he says. “We didn’t know when Hendrix was going to play and we decided to leave. He played like two hours after we left.”

(My comparable experience of bands missed — I never saw Nirvana play live. I was near the scene in Seattle for a while, but I was always broke, and it just never happened. But this isn’t about me…)

Back in the day Christopher hitchhiked from New England across the country with his basset hound, Scruff, to visit family in Portland, Oregon, and from there headed into California to visit friends. He has lived on both coasts, has always been off-beat, creative, and a bicycle-head. He and I agree that people drive too much and the world would be a much better place if everyone rode bikes more. Christopher went bike touring back when it was considered a pastime for hippies, weirdos, or financially unfortunate people who couldn’t afford to drive. Christopher was, and is, kind of a hippy and a weirdo — I say this only in the most endearing terms. It’s likely one reason he’s been a successful bicycle frame & fork fabricator for so long. Nobody overly “normal” seems to make it in this business.

That grin…

Christopher is one of the kindest, most big-hearted humans I know, and for him, people always come before work. Anytime someone stopped into the shop wanting to talk, he would set aside whatever he was doing, often times missing hours of work, just to be there for them. If someone needed a few dollars, more often than not he’d give it to them. He loves people, any and all kinds of people. And I think he loves it most when he can make someone smile.

And now…

The Welder

With Igleheart’s retirement the lineage of American bicycle frame building is passed down into the hands of the next generation of builders. East Coast builders, West Coast builders, in a lot of ways, these days, the internet brings us together. There’s Bilenky Cycles, Firefly, Chapman, Coast Cycles, Sycip, Curtis Inglis, Hunter, Rex, Breadwinner, Desalvo, Wolfhound, just to name a very few. And lest I forget, I’m a part of this list, too. We all come out of the history of it, taking our place. We’re in it as long as we’re in it, making it up as we go along, leaving traces of what we know in the bikes we build. It feels a little strange placing myself in this historic context, but here we are.

I feel very fortunate to have spent this much time with one of the old timers. Christopher has a wealth of knowledge, of inside stories, the history of bike people and of the craft. Even most of his tools hold stories, where they came from, who made them, who used them before. And I’d say, perhaps equally as important as his contribution to frame building is his unacknowledged role as Bicycle Ambassador. He’s brought many bicycles into being and he’s brought the joy of cycling to the world around him, every single day, literally for decades. This is just who he is. In so many ways he’s a mentor for the rest of us bike folks, and for humans in general. Christopher exemplifies the youthfulness and curiosity that comes with getting out and pedaling, breathing in the environment, finding joy on two wheels.

Bike Heads: Jrdn Free (red), Igleheart (blue). The photo in Jrdn’s hands is of Alex Singer in his workshop in France

It’s hard for me to think about what life is going to be like at the shop once Christopher has moved on. His goofiness, his impish laugh, his lightness of being. He’s been such a close companion and work mate for so long that his presence at the workshop on Page Street is, for me, integrated into the walls and the mess of tools & machines. Without him around I imagine it’s going to feel pretty hollow. Kind of like it feels at the end of the workday when we stop the music — the whole vibe changes.

Christopher didn’t know what it was, but he knew that I was writing something about his leaving, and every time I asked him questions about some detail from his past he’d say jokingly, “Oh, is this for my obituary?” For years, since I’ve known him, one of his favorite phrases when talking about being such a long-time bicycle frame builder is, “Not dead yet!” That’s right, man, you aren’t even close.

As a builder, as a friend, as a human being, I admire him tremendously. He’s messy as hell, but he’s the sweetest man you’ll ever meet. And I admit, I’m kind of jealous he’s moving to France. That’s not going to suck, not even a little bit.

The End is the Beginning

You are going to be missed, my Dear Friend, but I’m also so very happy that you & Fran are headed out on this new adventure. You’re going to have to put up with me soon enough when I bring a bicycle over and visit. I’m excited to share a plate of oysters with you and then go on a ride, let you show me around your new town and the French countryside. It’s gonna be wicked-pissah!

(Did I say it right?)

Below: Video love for our friend Jude: Ahearne (earmuffs), Igleheart (welding helmet)